Research trip for Miss Violet and the Great War

Where to begin? That’s what the history begs, as the history does not begin with one date in 1914 and ending in a date in 1918 – it does not bear one year, one single identiy, one particular flag (while it would choose the French flag if it had to choose) but it is a graveyard turned verdant – a word very near to its name.

I mustn’t neglect the journey on the rails to Verdun; a simple yet remarkable foray. En route to Verdun one sees field after golden field; the hills a particular yellow, a Van Gogh yellow. A crow on a hay-bale conjured up countless museum images and the impressionism of a master painter was translated into reality. I saw with Vincent’s eyes, his palette. We passed a whole vast plot of sunflowers, a transporting sight that connects me not only to Van Gogh but this sea of bright flowers also startlingly reminds me that I’d written about just such a field in my upcoming novel. In The Perilous Prophecy of Guard and Goddess the Goddess offers her Guard a glimpse of when she first met Phoenix; in a field of sunflowers arranging their seeds into iterate patterns. It was as if I knew that field before I’d ever seen it.

Arriving into the heart of Verdun, the first thing I see is a warrior-angel towering over the city, sword strong in her folded arms. She stands over la

Rue de la Victoire and her declaration of victory is stern, not joyous. She is flanked by canons and she reminds you of death and war. She is a god not to be trifled with and you can see her from every city vantage point. She pierces above the 14th century turreted city gates, watching. Warning. "Seven hundred thousand..." she murmurs.

Rue de la Victoire and her declaration of victory is stern, not joyous. She is flanked by canons and she reminds you of death and war. She is a god not to be trifled with and you can see her from every city vantage point. She pierces above the 14th century turreted city gates, watching. Warning. "Seven hundred thousand..." she murmurs.Transferring to a bus that takes tourists to World War I sites, monuments and forts, it is very clear that within its life and charm, Verdun remains a city of memorial. And it has just cause for grief nearly a century old. The most costly battle of the entire War to End All Wars, Verdun saw 700,000 dead, directly in the middle of the war, 1916. Its land, while overgrown with grass, trees, wildflowers, in many places remains jagged and unnatural, the work of bombs, mines and innumerable shells. The earth still bears the scars.

But it is a pocked landscape transformed green. Life will out, I was reminded, as swallows had reclaimed Fort Douaumont as their own, chirping and diving, nesting and flocking, these birds found the cool, dank fort a haven, turning what to humans appeared a bastion of hell, into a place that sheltered fragile, avian life.

Sorting through my notes from the fields and furrows, words are more raw than I'm used to. I stood drinking in what was once a “lunar landscape” of mud, shells fell like rain and opened violent craters. Though the land is blanketed again with green, the disconnect remains between the verdant carpet and the stories of the heart of the battle, when trenches were dug and yards were gained and lost. A small village named Fleury changed hands a heartbreaking number of times before being wiped from memory, existent now only in plaques and in honour. You can walk the two main streets of what was once Fleury,

now forested and green. You can still see some rubble in the uneven, cratered land. Markers tell you where the baker shop stood, the butcher, the shoe-maker, the well, the farms. It is a ghost town in the truest sense. On that ground families shot bullets from their basements- when there still were structures for shelter. It is nearly impossible to reconcile these disparate realities, but through imagination one can layer images upon one another like two separate photography slides; one slide reveals the loud destruction, exploding shells, rubble as far as the eye could see, dead bodies, the heart of a village ripped open and destroyed. This plate you struggle to place atop what is really staring you in the face; a quiet forest of pine, the sound of birds chirping – hardly a more peaceful place, the din of war seems impossibly far. Only those unnatural pockets and furrows of a ground landscaped by pummeling bombs remains to link these two disparate architectures together.

now forested and green. You can still see some rubble in the uneven, cratered land. Markers tell you where the baker shop stood, the butcher, the shoe-maker, the well, the farms. It is a ghost town in the truest sense. On that ground families shot bullets from their basements- when there still were structures for shelter. It is nearly impossible to reconcile these disparate realities, but through imagination one can layer images upon one another like two separate photography slides; one slide reveals the loud destruction, exploding shells, rubble as far as the eye could see, dead bodies, the heart of a village ripped open and destroyed. This plate you struggle to place atop what is really staring you in the face; a quiet forest of pine, the sound of birds chirping – hardly a more peaceful place, the din of war seems impossibly far. Only those unnatural pockets and furrows of a ground landscaped by pummeling bombs remains to link these two disparate architectures together.In Verdun I learned a new word. Ossuary. Visiting this repository, a tomb of the unknown soldier housing at least 130,000 unnamed bones, I would never be the same.

A field- a tunnel- a hall- a wall- a pit- a vast mansion of bone. Staring at the femurs stacked to my height for a countless number of square feet, carefully interlocked like log cabin timbers, I knew, staring into those square panels at the base of the monument that if I took a moment, even one moment to then process what I am writing now I would have broken down before countless other similarly stoic, awed, somber, stunned tourists. All of us putting our hands out – first to shield the sun and the light so that we might see into the pit of anonymous bone, and then the hand out became a distancing tool. Perhaps a primitive instinct to detach, to keep the disturbing vision at literal arm’s length. Trying not to imagine our own skeletons in such pieces, added to the mass, our hands remain out trying not to imagine that flesh once decked those bones. The pure essence of life that once animated those hundred-thousand bones would have taken a monument twice the size were the pit filled with bodies... It is hard to reconcile the flesh with the bone when we see them so separated. It is foreign, not of us, of an entirely separate time and place, it takes time to separate flesh from bone- through a horrifyingly organic, disturbing process. We see these bodies now pure, stripped of their flesh and in pieces they are dehumanized and yet we all can recognize them as the building blocks of ourselves.

Some bones are more of a trigger than others. For me, the interlocking femurs. For my father, the jaw bones, separated from the skull and tossed in a silent heap, baring their teeth to the stagnant air of their mass grave. The mind separates these images, compartmentalizeds them safely to assure that sanity and sense remain intact.

Was this the same France as golden fields and sunflowers? I read about France, I knew a deal of Paris and about art. I know what Victor Hugo wrote and Debussy composed. One feels one knows a country by its art, its books, its dance and music. But knowing its bones is another country entirely.

The 'undiscovered country' indeed. All of it France, and all French beauty may be found in Verdun, the banks of the Meuse no less beautiful for the monument of bones. More beautiful, perhaps, for the contrast. And as it appears to have been intended by the Ossuary's founders and builders; a reminder. A cautionary tale of war, whether world leaders hear it or not. Those who visit do.

---

Update 11/2018

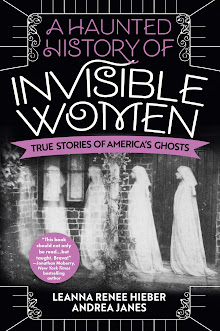

After a long and winding trial and tribulation of publishing, this research finally led to Miss Violet and the Great War, releasing 2/2019 from Tor Books

The 'undiscovered country' indeed. All of it France, and all French beauty may be found in Verdun, the banks of the Meuse no less beautiful for the monument of bones. More beautiful, perhaps, for the contrast. And as it appears to have been intended by the Ossuary's founders and builders; a reminder. A cautionary tale of war, whether world leaders hear it or not. Those who visit do.

---

Update 11/2018

After a long and winding trial and tribulation of publishing, this research finally led to Miss Violet and the Great War, releasing 2/2019 from Tor Books

6 comments:

Starkly beautiful, powerful & poignant. Thanks for sharing.

Leanna, I've spent most of my life trying to come to terms with the catastrophe of the First World War, after reading Vera Brittain's TESATMENT OF YOUTH in college. In America, WW1 tends to be treated as something of a footnote, a prelude to the Second World War, in which the US played a much larger role; in Europe and elsewhere, the wholesale slaughter that took place between 1914-1918 informed everything that came after: war, diplomacy, even modernity itself. Once it's in your blood, you never let go.

Thanks so much on a marvelous, sensitive and powerful post.

A somber and eloquently written reminder of the darkness that is war. Thank you.

P.S. You should think about writing a book someday. Ever consider being an author? :-) Sorry, had to toss in a little levity, because, after all, it's you, wonderful, unique you! BTW, congrats on finaling in the Maggies, it's an honor to be in the same category as you. Good luck!

Heartbreaking, lovely prose to describe such horrors. May we never forget.

Leanna, I'm almost crying IMAGINING. My word, it's just so...terrifyingly horrid. I mean, I've seen the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington (probably one of my most sobering moments), but seeing the actual bones of the unnamed people - that's unimaginable. And I agree that we think we know a country based on it's Art of any kind, but we really don't. We make assumptions and jump to conclusions sometimes, but seeing things and hearing about them are two completely different things.

Thanks for sharing this with all of us. My great-uncle was one of the unnamed soldiers from the Korean war, so this really made me think. I mean, imagine having some family desent from that part of France and seeing that. I mean, that could've been "your" relatives, you know?

With love,

Hanna

Thank you everyone for your thoughts and your heartfelt responses, I am blessed to hear your voices here, each one of you adding to this post with your own eloquent and powerful words, thank you.

Post a Comment